Eugene Onegin é

uma ópera de P I. Tschaikowsky com

libretto do compositor e de Konstantin

Schilowsky, segundo uma obra de Puskin. O enredo pode ler-se aqui.

O que ficou desajustado foi toda a história original, o amor

das irmãs Olga e Tatiana por Lenski e Onegin, com particular ênfase na cena

final entre Onegin e Tatiana que, neste enquadramento, não fez qualquer sentido.

No início estamos numa grande sala de jogos e está uma

televisão ligada, a emitir a preto e branco um campeonato de patinagem

artística. Nessa mesma televisão aparecerá mais tarde a chegada do Homem à lua,

a mira técnica e até o “granulado” da falta de emissão a meio da noite, quando

Tatiana não consegue dormir. Na célebre cena da carta, Tatiana dita-a para um

gravador em vez de a escrever e manda a gravação num envelope a Onegin.

Na festa de Tatiana, um dos números para divertimento dos

convidados é uma cena de striptease masculino. O duelo entre Onegin e Lenski

(mortal para o último) é um disparo à queima-roupa na cama onde ambos dormem.

O início da segunda parte abre com cowboys dispersos pelo

palco, alguns em tronco nu. O mau gosto surge enquanto Lenski canta a famosa e

belíssima ária Kuda kuda. antes de

ser morto e, no fundo do palco, os cowboys, numa bomba de gasolina, divertem-se

sexualmente com uma boneca insuflável. Já perto do final, entram em palco

vestidos de mulher e de saltos altos. Opções de gosto muito discutível e que não

trazem nada de inovador.

O tenor eslovaco Pavol

Breslik interpretou Lenski com grande nível. A voz tem um timbre bonito,

ouve-se bem sobre a orquestra e não perde qualidade quando sobe às notas mais

agudas. O cantor também tem uma boa figura, o que o ajudou na parte cénica.

Deixei para o fim o Eugene Onegin do barítono inglês Simon Keenlyside. É um cantor de que

gosto muito mas, aqui, foi a sua interpretação que menos me impressionou. Achei

que esteve sempre tenso e inseguro. O seu barítono é de elevada qualidade mas não

o demonstrou nem brilhou. E, cenicamente, também ficou muito aquém do habitual.

Esteve sempre estático, não demonstrou a agilidade e as excelentes qualidades cénicas

que o caracterizam.

***

Eugene

Onegin, Bayerische Staatsoper, March 2012

Eugene Onegin is an opera by P. I. Tchaikovsky with libretto by the composer and Konstantin Schilowsky, a text of Pushkin. The plot can be read here.

Eugene Onegin is an opera by P. I. Tchaikovsky with libretto by the composer and Konstantin Schilowsky, a text of Pushkin. The plot can be read here.

The staging

of Krzysztof Warlikowski brought the

action to the decades of 60-70 of the last century and was centered in a

homosexual relationship between Eugene Onegin and Lenski. This approach could

be prone to the presentation of scenes of vulgar content (as witnessed in the

opera Macbeth I saw the day before), but this has not happened in excess.

All that was the original story was misfitted, the love of sisters Olga and Tatiana by Onegin and Lenski, with particular emphasis on the final scene between Onegin and Tatiana. In this scenic option, it made no sense at all.

All that was the original story was misfitted, the love of sisters Olga and Tatiana by Onegin and Lenski, with particular emphasis on the final scene between Onegin and Tatiana. In this scenic option, it made no sense at all.

But there

were some interesting scenic details: At the beginning we are in a large game

room and a television is on, broadcasting a figure skating championship in black and

white. Later will appear, in the same television, the arrival of man to the

moon, the television test card and even the "grainy" of the lack of

emission at the middle of the night, when Tatiana can not sleep.

In the

famous letter scene, Tatiana dictates the text to a tape recorder instead of

writing and puts the recording in an envelope to be sent to Onegin.

At Tatiana´s party, one of the entertainment moments is male striptease performance. The duel between Onegin and Lenski (deadly for the latter) is a gunshot on the bed where they both sleep.

The beginning of the second part opens with cowboys scattered across the stage, some bare-chested. Another bad scenic option comes as Lenski sings the famous and beautiful aria Kuda kuda before being killed. In the background, the cowboys are in a gas station, playing sexually with an inflatable doll. Toward the end, they come on stage dressed as women with high heels. Questionable options that do not bring anything new to the stage.

At Tatiana´s party, one of the entertainment moments is male striptease performance. The duel between Onegin and Lenski (deadly for the latter) is a gunshot on the bed where they both sleep.

The beginning of the second part opens with cowboys scattered across the stage, some bare-chested. Another bad scenic option comes as Lenski sings the famous and beautiful aria Kuda kuda before being killed. In the background, the cowboys are in a gas station, playing sexually with an inflatable doll. Toward the end, they come on stage dressed as women with high heels. Questionable options that do not bring anything new to the stage.

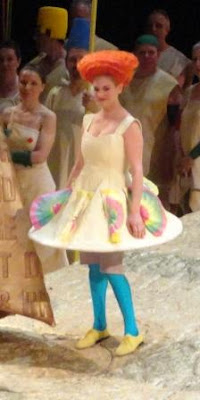

Tatiana was

Russian soprano Ekaterina Scherbachenko.

She was, by far, the best singer of the night. The voice is unusually beautyful,

very melodious, strong when needed and always high quality. On stage the

singer had an irrepressible presence. SShe conveyed anguish, despair and resignation whenever necessary. The

slim, tall figure of the singer also helped a lot. Fantastic.

Slovak tenor Pavol Breslik was a high quality Lenski. The voice has a beautiful tone, is heard over the orchestra and does not loose quality when singing top notes. The singer also has a good figure, which helped in the artistic part.

Slovak tenor Pavol Breslik was a high quality Lenski. The voice has a beautiful tone, is heard over the orchestra and does not loose quality when singing top notes. The singer also has a good figure, which helped in the artistic part.

Estonian bass

Ain Anger sang very well his aria in

Act 3, showing a powerful voice with a and very nice tone.

Secondary roles of Olga (Alisa Kolosova) Larina (Heike Grotzinger), Filipjewna (Elena Zilio) and Triquet (Guy de Mey) were all ok.

Secondary roles of Olga (Alisa Kolosova) Larina (Heike Grotzinger), Filipjewna (Elena Zilio) and Triquet (Guy de Mey) were all ok.

I left English baritone Simon Keenlyside’s Eugene Onegin for the end. Keenlyside is a singer that I like very much but here his interpretation did not impressed me. I found him always tense and insecure. His baritone is high quality but he did not show it and he was not brilliant. And, artistically, he also also not as well as he usually is. He was always very static, and he did not show the agility and the outstanding artistic qualities that characterize him.

***

***

***